From Kyoto to California: The Evolution of Japanese Buddhism in America

To understand Japan is to understand that Buddhism here is not a "religion" in the Western sense of a Sunday obligation. It is the very marrow of the bone. It is the tilt of a bow, the steam rising from a ceramic tea bowl, and the relentless, quiet precision of the Shinkansen.

The Architects of the Japanese Soul

The tapestry of Japanese Buddhism wasn't woven overnight; it was engineered by titans who saw philosophy as the ultimate tool for nation-building.

Prince Shōtoku (574–622): The founding father of Japanese Buddhism. He didn't just build temples like Hōryū-ji; he used the Dharma as a legal and moral framework to unify a fractured land.

Kūkai (Kōbō-Daishi): The polymath who brought Shingon (Esoteric) Buddhism from China. He turned Mt. Kōya into a celestial city and taught that enlightenment could be found "in this very body."

Dōgen Zenji: The 13th-century monk who founded Sōtō Zen. His obsession with shikan-taza (just sitting) redefined the Japanese relationship with time and task. For Dōgen, peeling a radish was as sacred as chanting a sutra.

The Anatomy of Presence: Health, Mood, and the "Zen" State

This immersion in Buddhist thought has created a unique national temperament. It isn't that the Japanese are inherently calmer—anyone who has seen Tokyo at rush hour knows otherwise—but there is an underlying cultural philosophy of Ma (the space between) and Wabi-sabi (finding beauty in the fleeting and flawed).

The Health of Impermanence: The concept of Mujō (impermanence) acts as a psychological buffer. When you accept that all things fade, the stress of holding onto youth or status diminishes. This contributes to the world-leading longevity found in Japan; it is a heart at peace with the seasons.

The Ritual of Greeting: The Ojigi (bow) is a physical manifestation of the Buddhist belief that the "Buddha-nature" in one person is recognizing the "Buddha-nature" in another. It’s a constant, micro-meditation on humility.

The Great Migration: From Hiroshima to the Haight-Ashbury

The narrative took a cinematic turn after 1945. Following the devastation of World War II, the relationship between the U.S. and Japan shifted from bitter enemies to a strange, symbiotic fascination. As American GIs returned home, they brought back more than just souvenirs; they brought a curiosity for the "East."

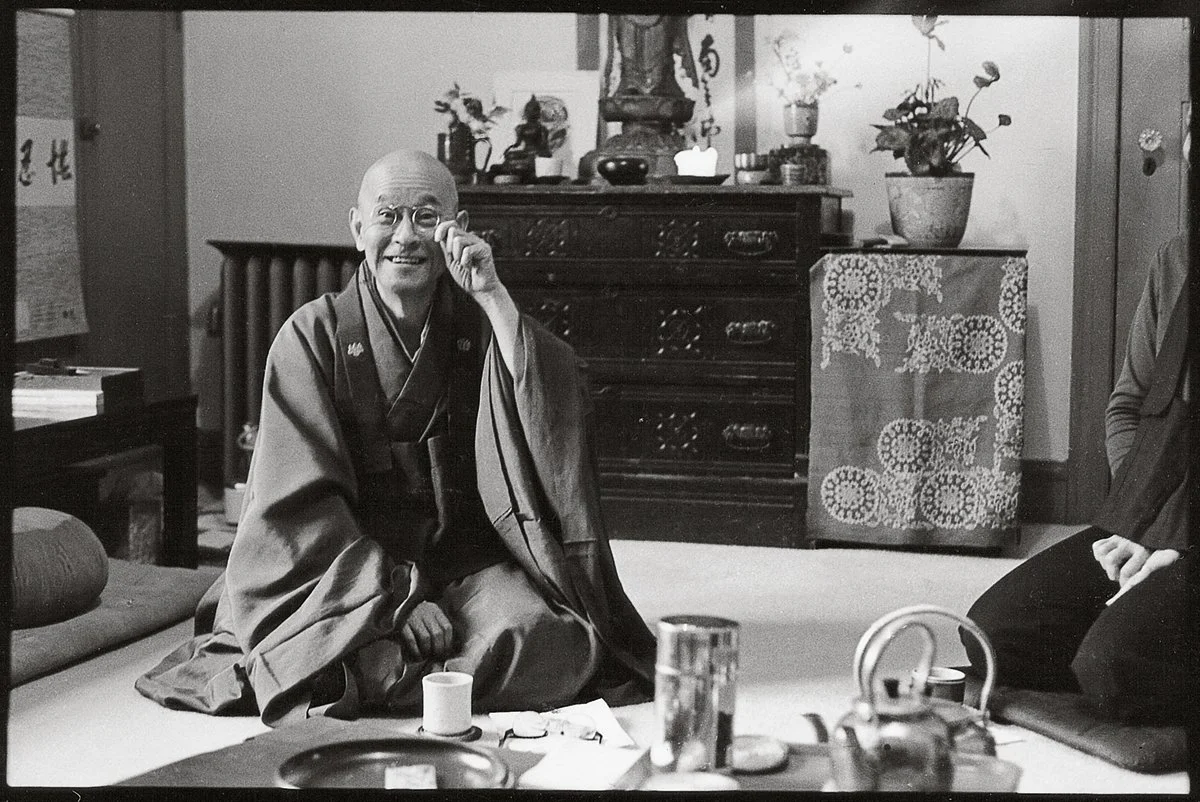

The real catalyst, however, was the influx of Japanese teachers to American shores. Figures like Shunryu Suzuki (author of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind) arrived in San Francisco, not to convert, but to sit.

Suddenly, the rigid, post-war American psyche was introduced to the concept of the "Empty Mind." By the 1960s, the "Beat Generation"—Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Alan Watts—had hijacked Zen, turning it into the ultimate counter-culture accessory. Japan’s ancient austerity became the soundtrack to America’s psychedelic awakening.

The "Aesthetic" Trap: Where We Stand Today

Today, Buddhism in the U.S. is everywhere and nowhere. We have "Zen" spas, "Buddha" bowls at fast-casual restaurants, and $120 yoga mats etched with sacred mandalas. It has become a lifestyle brand—a "quasi-Buddhist" aesthetic that prizes the calm without the discipline.

In America, we often treat Buddhism like a pharmacy: we go there to get a "prescription" for stress. In Japan, it’s not a pill; it’s the air. We have the "knock-off" culture—meditation apps that promise productivity rather than the ego-dissolution that actual Buddhist practice demands. We are connected to the imagery, but we are still largely illiterate in the philosophy.

Culture Shock - An Integration Guide:

If you want to move beyond the "Zen" candle and actually invite Japanese Buddhist philosophy into your life, it requires a shift in how you move, not just what you buy.

Practice Soji (Mindful Cleaning): In Japanese monasteries, cleaning is not a chore; it is practice. Spend 10 minutes cleaning a corner of your home with total focus. Don't listen to a podcast; just listen to the scrub of the brush.

Adopt the "Beginner's Mind" (Shoshin): Approach your most routine task—making coffee, driving to work—as if you have never done it before. Strip away your expertise and just observe.

Create a Space for Stillness: You don't need an altar. You need a dedicated spot where you sit for five minutes a day, facing a wall or a window, doing nothing but breathing.

Embrace the "Ichigo Ichie": This translates to "one time, one encounter." Treat every meeting with a friend or a stranger as a once-in-a-lifetime event that will never be repeated exactly this way again.

The beauty of Japanese Buddhism is that it doesn’t ask you to leave the world; it asks you to finally show up to it.